- Home

- Janina Matthewson

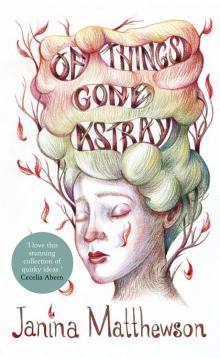

Of Things Gone Astray Page 2

Of Things Gone Astray Read online

Page 2

The air was clear and easy to breathe, and Robert felt energised and enthusiastic as he jogged past the silent houses on his street.

After half a mile a frown crossed his face. This was harder than he’d thought it would be.

He jogged onward.

He reached a nearby park and slipped inside to run on the grass, feeling a moment of relief as his knees registered the absence of concrete. Then he promptly developed a stitch.

He came to a panting halt and bent over, clutching his sides. Taking a couple of breaths, he staggered on.

By the time he got back home, his face was red and streaming and he was limping. He stood outside the house for two minutes, arms akimbo, gasping for air, before he opened the door and dragged himself upstairs. As he walked into the bedroom Mara stirred and opened her eyes. She blinked at him a couple of times and burst out laughing.

Robert poked his tongue out at her and headed for the bathroom.

‘You shouldn’t laugh you know,’ he said over his shoulder. ‘This is me recognising the need to hang onto you by maintaining a slammin’ bod.’

‘Oh god, please don’t take my laughter as a sign I’m not grateful.’

‘I’ll fill your grate,’ Robert said. ‘Be quiet and let me shower, woman.’

He could hear Mara chuckling into her pillow as he closed the bedroom door on her, trying to make sure she didn’t see him wince.

Marcus.

BIRDS. DIDN’T FEEL LIKE TIME yet. Didn’t feel late enough for birds. But there they were, so that was that. Birds could sense time better than him, so they must be right.

He opened his eyes. Ah. There was the problem. The blinds were down. He usually slept with them open, he usually woke with the light.

Strange. That they were closed.

He sat up and slid on his glasses. He crossed to the window and opened the blinds. It was later than he’d thought. It was later than he usually woke up. It was much later.

He had a routine for the mornings. Always the same. A light breakfast of fruit. A full breakfast later, after some time in the music room. Now it wouldn’t work. Now it had gone wrong. It was already too late.

He went downstairs and stood in the kitchen. He was hungrier than usual. He opened the fridge and took out the eggs.

It wasn’t until almost eight o’clock that he made it to the music room. Much later than normal.

The music room was the nicest room in the house. It was the most important place in the house. Floor to ceiling windows along two walls. Lots of light. He liked lots of light to practise, although when he performed he always requested that the stage be kept as dim as possible. People should be listening, he said, not looking.

When he had performed. When he used to perform. It had always seemed important.

There were few decorations, nothing to distract him. The rest of the house was covered in pictures, in paintings and photos and sketches. Not here. Just one small photo of Albert propped on top of the shelf by the door.

The piano stood in the middle of the room.

He walked around it a couple of times, as he always did. He closed his eyes and threw his head back. He breathed deeply, and sat down.

He rested his hands for a moment on the cover before lifting it.

He stared. His hands, always so reliable, began to shake.

The world had ended. His life had ended.

Jake.

Jake stands on the footpath facing his house. His schoolbag is heavy because of all the library books his mother has finally remembered he has to take back.

No, that wasn’t right. He hadn’t been going to school that day. If he’d been going to school he would have been there already, for hours.

Jake stands on the footpath facing his house. The street is quiet for a Saturday. Because it isn’t Saturday. It’s Tuesday. It feels like Saturday to Jake because he’s not wearing his school uniform. He’s not going to school.

Why was he not going to school? It wasn’t the holidays.

He’s not going to school because he has a doctor’s appointment about his foot and then his mum is going to take him to McDonald’s for a sundae. He wonders if she’ll let him have one with a flake.

He is sweating. He is sweating because it is very hot. The sun is big and bright above him and seems to be soaking him right through to his bones. Deeper than his bones. He wishes he was wearing jandals instead of lace-up shoes. His mum doesn’t like him to wear jandals anymore because she likes him to always wear his orthotics. Jake looks down at his feet and frowns. He hadn’t thought his feet would betray him like this. He’d thought they were allies.

He wishes his mum would hurry up. She’s gone back in to the house because she forgot to bring –

What? What had she forgotten?

She forgot to bring something for the smiling lady that had visited last week. She promised to drop something off to her and she’s annoyed about it.

Jake’s mum is also annoyed that they have to go to the doctor’s at midday. When they’ve gone before it’s always been after school but she couldn’t get an appointment with the doctor because the doctor’s about to get married and go away, Jake thinks perhaps forever. He thinks that maybe if the doctor gets married and goes away forever he’ll be able to stop wearing his orthotics and his mum won’t be able to tell him off.

Jake has been waiting for a long time. He thinks perhaps seven hours. He wonders if his mum would notice if he snuck past her upstairs and put on his jandals.

When the ground moves, he isn’t scared. It does that a lot and all that happens is his cat will run all over the house really fast. Jake thinks that is pretty funny.

He doesn’t expect the house to fall down like it does.

Jake lay still on his bed for a while. He didn’t think he was right about it being that hot. He thought he was right about most things, but he didn’t think it had been hot that day.

He didn’t feel much like going downstairs. On this day two years ago his mum had made waffles with bacon and banana and syrup for breakfast, with a candle sticking out of one of the waffles.

Jake didn’t think there would be waffles this morning.

He didn’t think there would be waffles any morning.

Delia.

AFTER A WHILE DELIA GLANCED at her watch and swore. She’d been gone longer than she should have, naturally. Until a few years ago Delia had never been late, not once in her life, now it happened all the time. Not that there ever was anything in particular to be on time for now, but she didn’t like to be so long away.

As she walked down the street, however, her pace slackened. She couldn’t help it. She knew that once she got home, it was unlikely she’d get another chance to go out. There was always so much to do, incidental, unimportant things to do: cups of tea to make, lunch to prepare, washing to fold, all the things your average housewife usually had to do.

She could never go off for too long without worrying that something would go wrong, that her mother would need help and be alone, but being in the house sometimes became intolerable. Resolving that ten extra minutes now would help maintain her equilibrium for the rest of the day, she allowed her pace to slow to a light meander. As she walked, she convinced herself that her mother would probably not get out of bed until she was home in any case.

It was still early enough for the streets to be quiet; there were just a few joggers, the keys in their bum pockets jingling slightly as they ran, and some tired-looking besuited men who probably didn’t need to spend as much time at work as they thought.

Delia breathed deeply as she went, savouring the bright morning air. Again, she paid little attention to her specific route, veering down streets at random, looking at houses she didn’t know. She stopped to look at unusual trees and flowers in people’s gardens, and spent a while trying to get a reluctant cat to approach her.

The sky grew ever brighter, the day was warming, the clouds were moving on.

Delia reached a church she didn’t know an

d she suddenly felt disconcerted. She should be nearly home by now, there shouldn’t be any churches she didn’t know.

She looked around her. She’d been walking in the right direction, she was sure of it, but she suddenly realised that it wasn’t just the church – she hadn’t recognised anything in ages. She shook her head and pressed on. She must only be a couple of streets away; she’d find herself soon.

Mrs Featherby.

MRS FEATHERBY HAD BOILED THE kettle four times whilst waiting for the police constable to arrive. Although she told herself she wanted to be prepared, she also wanted to avoid being the spectacle she knew she’d become. The kitchen was out of sight of the absent wall.

People were beginning to walk along the footpath and, as she had expected, they were staring. Those walking in pairs stopped and muttered to each other. She saw a few take pictures. She wanted to move out of their sight permanently, to live out the rest of her life in the back of the house, but she was afraid of missing the policeman when he arrived. It wasn’t as if he would be able to ring the doorbell, after all. She pursed her lips and moved to the kitchen to boil the kettle once more.

When he did eventually arrive he stood on the footpath for what must have been a full two minutes, staring, saying nothing. He didn’t seem to notice Mrs Featherby at all until she stepped out into the garden and said, ‘Good morning, Constable.’

She supposed constable was still the correct term to use, although, in all honesty, he didn’t look much like her idea of a constable. He was of an age at which, according to Mrs Featherby’s ideas, a policeman ought to be married, but he was not wearing a ring. He seemed to be suffering from hay fever or a severe head cold, but he was neglecting to use a handkerchief. He arrived with a sandwich in one hand and continually took bites from it as he talked, inconsistently remembering to swallow.

He introduced himself as PC Grigson, gave a hearty sniff, whistled towards the general vicinity of Mrs Featherby’s house and said, ‘Not sure what I’m going to be able to do for you, love; it’s a builder you’re going to need.’

Mrs Featherby felt her brow furrow involuntarily at being called ‘love’, but she decided not to comment.

‘Obviously I shall need a builder to fix it, young man. You are here to tell me how it happened. You are here to find out who is responsible and see that the person, or persons, are brought to justice.’

‘Right,’ said Grigson, running a wrist under his streaming nose. ‘So you think we should be looking for a perpetrator?’

‘Naturally I think you should be looking for a perpetrator. There has been a theft. Someone has stolen the front wall of my house. I wish to see that person found and held to account.’

‘Only thing is, pet, I just don’t see how someone can have stolen a whole wall of a house.’

‘No, Constable, I’m sure you do not. No more do I. But I believe part of your job consists of investigating how mysterious occurrences have, in fact, occurred. You must find it out.’

‘Right,’ he sniffed again. ‘Sure. Tell you what, I’m going to give you the name of a builder. He’s my ex-wife’s cousin, as a matter of fact, but he is actually pretty good anyway, and quite reliable, did my bathroom a few months back, and if I give him a call to let him know you’re in need, he’ll bump you up the list.’ He paused and glanced at the gaping hole in the side of the house. ‘And I’ll have a look through recent records, see if any similar, ah, thefts have occurred in the area.’

‘So what am I to do?’

‘Oh, you know. Let us know if you think of any other information. If you remember seeing anyone suspicious hanging around, or if you see someone in the future.’

Mrs Featherby didn’t quite know how to point out that none of this was in any way useful to her or other potential victims. She elected not to offer PC Grigson a cup of tea.

The copper gave a final sniff, said a non-committal goodbye, and headed back to his car. Mrs Featherby stood alone in her fractured home, vainly attempting to disregard the whispers and stares of her passing neighbours.

Robert.

WHEN HE CAME DOWN TO the kitchen, Robert found Bonny sitting at the table, studiously drawing on one of the bamboo place mats.

‘Dad,’ said Bonny, fixing Robert with a serious gaze. ‘Can I do something different with my cereal today?’

‘What did you have in mind?’

‘Well, instead of having just one kind of cereal, can I have cornflakes and coco pops mixed all together?’

‘That is an excellent idea, Bonny. I’m going to do the same. Would you like a banana sliced on top of yours?’

‘Um, not so much. Can I have a banana just on its own?’

Mara walked into the kitchen as they were eating. She had dressed, but not yet done anything with her hair, which stood out from her head in a wild mane of tawny brown. Robert stood and walked over to her. He twisted his hands into the mass of hair and kissed her.

‘Nice of you to wait till you’d showered before doing that, my love,’ she said.

‘Anything for you.’

‘I’m glad you feel that way,’ said Mara, concentrating harder than was strictly necessary on the cup of coffee she was pouring. ‘I’ve been asked to go in to see Bonny’s teacher this afternoon. Can you come?’

‘Do they need both of us?’

‘No, they didn’t say that, it’s just that I’m nervous and I’d rather not go alone. It’s the first time I’ve been called in to see a teacher and I don’t know what they want. I’m worried I won’t act like enough of a grown up.’

‘If it were next week I probably could. I’ve a lot on at the moment. A few people are away at a conference, you know, and we’ve taken on a couple of important new clients. You’ll be fine. They’re used to dealing with children, after all. Or can you move the meeting?’

‘Next week something else will come up and you still won’t be able to go.’

‘You can’t be sure of that.’

‘I am 87 per cent sure of that … 87 and a half. There is always something that needs to be done, and it always needs to be done by you because you’re a big girly swot who can’t delegate.’ She rubbed her eyes and took a sip of her coffee. ‘It’s fine,’ she said. ‘I can go alone. It’s probably no big deal.’

‘You sure?’

‘Yes, I’m sure, whatever; your job can’t be arranged to suit your convenience. Mine can.’

Robert kissed her.

‘Don’t think I don’t envy you that, by the way.’

‘Oh, you’ve no idea,’ said Mara, speaking right into his ear, all low and suggestive. ‘I can work naked if I want.’

‘Bloody hell, Mara,’ Robert muttered back. ‘And with that image I have to leave. To go to my office. The land where nakedness is a crime. Why didn’t I become a website designer? You lot have it so damn sweet.’

‘Please. You couldn’t handle it. And you’ve terrible taste.’

‘Ooh, right in the feelings.’

Mara gave a bloodthirsty chuckle and ruffled Robert’s hair as she walked past him to the cereal.

Robert grabbed his bag from the lounge and headed for the front door.

‘Babe,’ Mara called from behind him. Robert turned to see her standing in the hall holding her shirt open.

‘Mum, can I have a juice?’ Bonny called from the kitchen. Mara poked her tongue out and turned to go back to their daughter.

‘Bloody hell,’ Robert said again as he turned and stepped out into the world.

Jake.

JAKE TRIED HIS HARDEST NOT to expect waffles when he walked into the kitchen, and it was a good thing he did. His dad was eating cereal standing up, staring into the small, overgrown garden. Jake chewed his lip and crossed to the cupboard to look for bread. There were only two pieces left and one of them was an end. He sighed and immediately regretted it. He hated it when people sighed. His dad never sighed, although you’d think he had plenty of reason to. Jake put the bread in the toaster.

‘Good mornin

g,’ his dad said while Jake was spreading peanut butter on his toast. Jake wondered if it had taken him that long to notice him, or just that long to remember to say hello.

‘Hi,’ Jake replied.

‘Your teacher says you’re doing well at school. I called her last night to ask how things were going, how you were settling in.’

Jake had trouble remembering what it had been like talking to his dad before, but he was pretty sure they’d never had conversations like this. Had they talked about TV? Did they tell each other jokes?

‘I guess so,’ he said. ‘I have a spelling test today.’

‘Good,’ said his dad. ‘That’s good.’

Jake tried to think of something sensible to say. ‘How’s your work?’ he settled on with a tiny grimace.

‘Oh, fine. It’s fine. I should get started for the day, actually.’

Jake watched his dad walk out of the kitchen and head slowly to his office. He wondered if he should have had some kind of funny story from school. He couldn’t remember if anything funny had happened there recently.

He sat at the table and finished his toast. His dad had forgotten what day it was. He’d forgotten there was something to celebrate. Jake decided not to mind. He decided to try his hardest not to mind. He washed his dishes and went to his room to get his school bag.

Cassie.

CASSIE DIDN’T NOTICE AT FIRST when her phone started to ring. She didn’t hear it. At least, she heard it but it felt remote, even though it was in her pocket and vibrating as well as ringing; it wasn’t connected to her. It wasn’t until she saw someone staring at her that she realised she was supposed to do something about it. That it was hers.

She pulled out the phone, suddenly thinking that maybe it was Floss, that soon they would be laughing over whatever mix up it was that had meant they weren’t yet together.

Of Things Gone Astray

Of Things Gone Astray